Coffee Break: Armed Madhouse – How DARPA Lost Its Mojo

This article examines how the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) evolved from the most imaginative and consequential technological incubator in the United States to an agency constrained by political caution, industrial decline, and bureaucratic inertia. By contrasting its golden age—marked by ARPANET, stealth, GPS, and breakthrough computing—with its current era of unfielded prototypes and abandoned systems, we explore what changed in DARPA’s environment and why the agency no longer produces world-altering capabilities. The analysis centers on three structural failures: political interference, industrial risk aversion, and perverse incentives that reward programs for never reaching completion.

DARPA was created in 1958 in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s launch of the Sputnik satellite. DARPA’s mission was to restore U.S. technological leadership and ensure that the U.S. defined the frontiers of defense innovation. Operating outside traditional military service bureaucracy, it was empowered to make high-risk bets on long-horizon research, aiming not to refine existing systems but to invent entirely new categories of military capability.

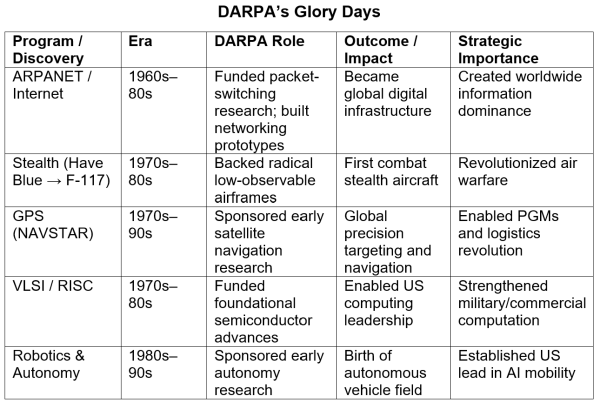

DARPA’s Golden Age

DARPA’s early decades from the 1960s through the 1990s were defined by an extraordinary ability to convert theoretical research concepts into functioning, world-changing systems. At the height of the Cold War, the United States maintained a dense constellation of industrial laboratories, elite universities, and high-talent engineering shops that could absorb DARPA’s experimental vision and transform it into working infrastructure.

ARPANET, the ancestor of the modern Internet, remains the clearest example: a long-horizon bet on networked packet switching communications that matured over subsequent decades into the public Internet, the backbone of the global digital economy. In this era, DARPA’s fundamental advantage was not talent, money, or secrecy, but its tight coupling to an industrial ecosystem capable of absorbing radical ideas and turning them into deployed military assets; it is a capability the U.S. no longer possesses.

ARPANET IMP – the start of something big

Have Blue prototype – precursor to F117

Political Restriction

DARPA’s mandate changed dramatically in the early 1990s when director Craig Fields was removed for expanding the agency’s work into dual-use, commercially relevant technologies, especially semiconductors. His ouster sent a chilling message: DARPA could innovate, but not in ways that reshaped America’s industrial trajectory. This shift reflected the ascendant neoliberal belief that government should avoid “picking winners and losers,” effectively barring DARPA from pursuing the ecosystem-shaping projects that had once engendered new industries.

Through the 1990s this constraint deepened, narrowing DARPA’s freedom to explore politically sensitive or industrially disruptive technologies. When the Total Information Awareness counterterrorism research program emerged in the early 2000s, the political backlash reinforced the limits already imposed. DARPA had managed TIA’s research office and funded advanced prototype data-analysis tools, but it never operated surveillance systems or ingested real personal data. Yet the controversy made clear that crossing political boundaries now carried institutional consequences. By the mid-2000s, DARPA was no longer permitted to act as an engine for national-scale technological advancement.

Industrial Decline

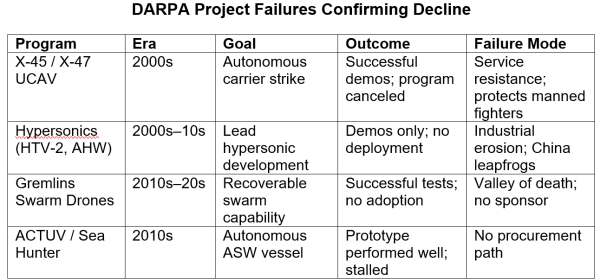

The collapse of America’s diversified industrial base and the consolidation of its defense contractors fundamentally altered what DARPA could accomplish. In the 1970s and 1980s, DARPA could hand a radically unconventional design to a firm like Northrop, Lockheed, or Hughes and expect rapid iteration by engineers empowered to take risks. Today, five mega-primes dominate the landscape; their financial models reward predictability, long contract cycles, and incremental improvements to legacy platforms. A revolutionary DARPA prototype now threatens, rather than complements, the revenue streams of the remaining mega-primes. As a result, many DARPA breakthroughs die not from technical failure but from a lack of industrial appetite to develop them into fielded systems. This is the second structural failure.

Perverse Incentives

DARPA can still generate astonishing prototypes, but the modern defense acquisition system no longer provides a pathway to transition them into actual capabilities. Programs that produce successful demonstrations—such as autonomous carrier aviation, hypersonic gliders, or autonomous surface vessels—often stall because procurement requires inter-service consensus, stable multi‑year funding, and the willingness to disrupt existing doctrine. The system now rewards starting programs, not finishing them; extending timelines, not fielding capabilities; and commissioning studies instead of building forces. This is the third and final structural failure: the emergence of a perverse incentive regime under which success is dangerous and failure is profitable.

The Valley of Death

Defense analysts refer to the treacherous gap between a successful prototype and a fully funded military program as the “valley of death.” In theory, DARPA hands off promising technologies to the services for adoption. In practice, the handoff has become nearly impossible. Modern acquisition rules require multi‑year budgeting, rigid requirements processes, and the alignment of service doctrine—all of which strongly favor established platforms over disruptive new capabilities. As a result, in recent years DARPA projects that demonstrate clear technical success often stall when no service is willing to sponsor procurement or restructure existing force plans. The valley of death has grown to the extent that it now functions as a structural barrier: a place where groundbreaking work is celebrated, briefed, and studied, then quietly set aside.

Case Study: The UCAVs That Worked

DARPA’s X-47 Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle program demonstrated that a stealthy, autonomous strike aircraft could operate from a carrier deck; execute coordinated missions; and, in contested environments, perform roles traditionally reserved for manned aircraft. Despite these impressive technical successes, the program died the moment it reached the transition point requiring service sponsorship. The Navy reframed the mission to emphasize surveillance over strike, protecting the budgets and institutional primacy of manned tactical aviation. With no service willing to champion procurement, the project fell into the valley of death. The parallel X-45 program for the Air Force, which had also demonstrated successful autonomous strike operations, met the same fate for similar reasons. Russia and China are both moving toward operational deployment of high-performance, stealthy UCAVs such as S-70 Okhotnik and GJ-11 Sharp Sword — precisely the category the U.S. pioneered with the X-45 and X-47 programs before canceling them.

X-47 UCAV – rejected by naval aviators

Russian Sukhoi S-70 Okhotnik UCAV – Note resemblance to X-47

Conclusion

DARPA’s decline is not the result of internal failure; it is the consequence of a deteriorating national defense ecosystem. In the era of ARPANET, the United States possessed the political confidence, industrial depth, and bureaucratic flexibility to absorb and exploit DARPA’s boldest ideas. Today, DARPA still dreams big, but those dreams now collide with political caution, industrial risk aversion, and perverse incentives that punish success and reward stagnation. DARPA’s innovative imagination remains intact. What has faltered is the country around it, which no longer possesses the institutional ability to turn breakthrough ideas into national capabilities.

Source link