‘Joy Within His House’: Making sense of life in a monastery

(RNS) — Sister Mary Magdalene of the Immaculate Conception Prewitt, a 38-year-old nun in the Dominican order, is often asked how she got from her upbringing in Kansas to life in a monastery in New Jersey. In a new book, “Joy Within His House,” Prewitt explains, tracing her path from college in Pittsburg, Kansas, to an enclosed monastery in Summit, New Jersey, where she spends her time in a community of women ages 22 to 93, give or take the occasional visitor exploring their own possible vocation to contemplative life.

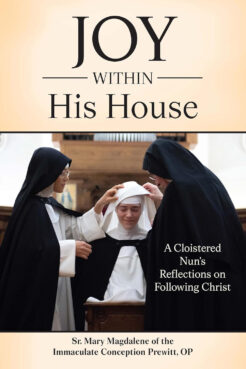

But the ambitious book about prayer, vocational discernment, and monastery life is much more than an autobiography. Instead, she offers a primer on what it means to lead a contemplative life in the Dominican order’s tradition, from the times of prayer to recreation to what it means spiritually to be cloistered. The volume includes evocative monastery snapshots from photographer Jeffrey Bruno.

She also cites not only a variety of Christian Scriptures, but Catholic teaching and a surprising number of novels. (Her top 10 list includes classics such as “Middlemarch,” “The Brothers Karamazov” and “Anna Karenina,” but also Sigrid Undset’s Nobel Prize-winning “Kristin Lavransdatter,” a historical trilogy about an unconventional young Norwegian woman set in the 1400s.)

Her hope in writing the book, she said, is to make the fundamentals of monastery life more accessible to laypeople. She writes about many familiar moments that the least religious readers can relate to, including medical check-ups and emergency care and grocery shopping. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What led you to write “Joy Within His House”?

People have so many misconceptions about the cloister. Part of the reason for wanting to write the book is really to help people to understand something that they don’t understand and often have erroneous ideas about, but also to give them the principles to grow closer to the Lord that the monastery has made so accessible.

What brought you to the monastery?

In college, I started thinking about what I wanted to do with my life. As I began spending more time in prayer, I started really asking the Lord what he wanted me to do with my life. I began to see the things I thought were where I wanted to go (but) I don’t think I would actually be happy doing. The unfolding of my vocation really took place by spending time in prayer and asking the Lord where he was leading me and seeing how I could be happy in this way of life, but also grow in holiness.

You’re very candid about both some of the adjustments needed to live in community, as well as the joys.

It wasn’t an adjustment. You have the same dynamics in family life. I had the same dynamic living in a college dormitory. The difference is that in a college dormitory, you’re not united in the single goal of union with God in the way you are in the religious life. In a lot of ways, it’s actually easier to have that basis for community.

Everyone has a different personality. Everybody does things differently. It’s good to be open and honest about that, to acknowledge the tension that arises on a natural level from that, but not to be caught up in it. I worked in a restaurant before I entered, and it was like the same kind of dynamic, but in a pressure cooker. People would get incredibly upset over the smallest thing. In religious life, it’s great to be able to rise above that. You don’t have those sorts of fluctuations in that way.

What makes your life different from that of a prayerful lay Christian?

All Christians are called to union with God. In a lot of ways, contemplatives, either male or female, are different because of the enclosure — the intentional separation from the world to focus exclusively on that goal. There are wonderful, beautiful opportunities intentionally built into the day to be set aside for prayer to be working for God, to be growing closer to one another in creation, and to focus on that goal.

How do you know what particular events or people to pray for?

It’s a matter of just listening to the Holy Spirit. You feel inclined to hold onto certain intentions. On a practical level, you can’t always be praying for everybody’s intentions — intentions have to either be general or specific. I can pray for all prisoners, but I can also think of this woman who is a friend of the community whose son is in prison. But it’s also just good to pray for those who need prayers. I think the Holy Spirit just really leads you in that way. Sometimes you can spend 10 minutes reading the prayer board, and there’s just one prayer that you really remember that really sticks to you. I think the Lord sorts all that out.

I was intrigued by the classic novels and works of great literature you mention in your book. Why did you include them?

Literature has a beautiful ability to speak to the realities of human nature. I think it’s important to hold that ability in its proper place. But it can speak to the commonalities of our human experience, right?

One of the most famous works of literature in human history is St. Augustine’s “Confessions.” That’s really the story of his life, but his experience is on every single page. The beauty of that work is that the entire thing is a prayer written to God, (yet) it is the rawness of Augustine’s experience that we’re allowed to enter into. I think literature especially has a way of capturing in art what we can’t sometimes explain.

Source link