“I was not fierce enough”: Georgian activist’s brutal confession as democracy collapses

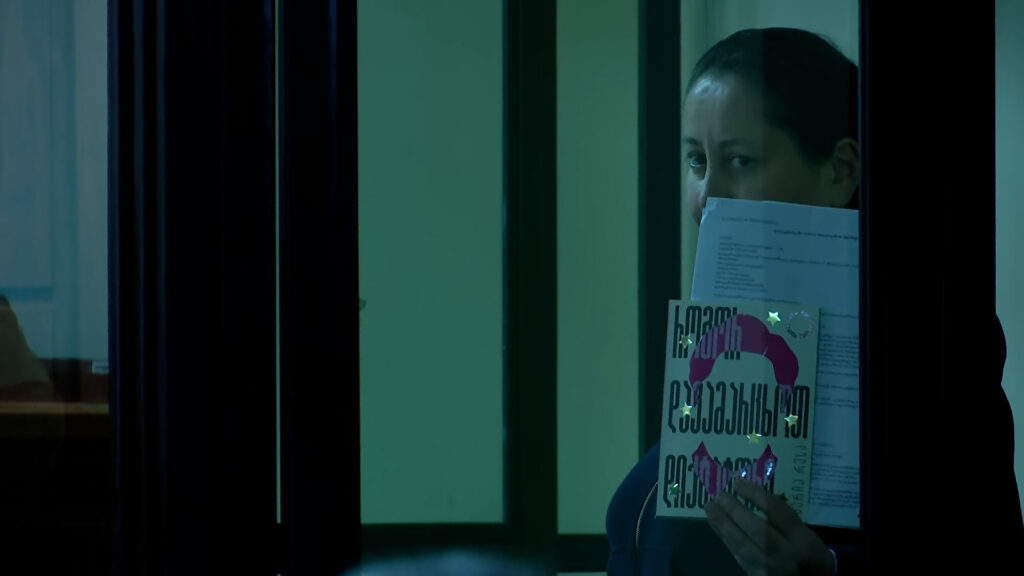

“We fucked up.” It’s not often you hear a democracy activist open with those words, but Nino Robakidze, a veteran democracy activist with over 15 years fighting for Georgian freedom, isn’t interested in pretty narratives.

Speaking at the “FuckUp Night” panel at the Lviv Media Forum 2025, Robakidze laid bare how Georgian civil society enabled the fastest documented democratic collapse in modern European history.

The timeline is breathtaking: December 2023, Georgia receives EU candidate status. Eighteen months later, dozens of political prisoners, including four high-profile politicians, fill Georgian jails, independent media faces criminal prosecution, and the government has abandoned European integration entirely. Over 200 public servants were fired simply for posting pro-European statements on Facebook.

“Georgian civil society is in a perfect storm,” she says. “We saw the red flags. We really saw the red flags. But it was so uncomfortable to really talk about that.”

From EU dreams to Russian nightmare in record time

Twenty-one years after the Rose Revolution promised Georgia a European future, the country has achieved something unprecedented: the fastest documented slide from EU candidate to authoritarian crackdown in European history.

The timeline is breathtaking.

- December 2023: EU grants Georgia candidate status.

- May 2024: Government passes Russian-style “foreign agent” law.

- October 2024: Elections marked by widespread fraud.

- November 2024: Government suspends EU talks.

- January 2025: First female journalist political prisoner.

The halt to EU accession talks were the straw that broke the camel’s back. Polls show 80% of Georgians want EU membership—one of the highest rates in any candidate country.

What followed was six months of non-stop protests across Georgia—unprecedented in the country’s history. Police have violently dispersed demonstrators using water cannons and tear gas against crowds singing the EU anthem.

Hundreds have been arrested, including Mzia Amaglobeli, co-founder of independent outlets Batumelebi and Netgazeti, who faces up to seven years in prison for symbolically slapping a police chief after he allegedly spat in her face and verbally abused her. She became Georgia’s first female journalist to be designated a political prisoner.

But Robakidze, former Country Director for IREX Georgia, isn’t just analyzing the crisis—she’s dissecting how democracy defenders like herself enabled it through a fatal dependency that made Georgian freedom hostage to foreign funding.

For two decades, the US government poured millions into Georgian civil society—building the independent media, NGOs, and democracy programs that became the envy of the former Soviet space. That investment created something genuinely remarkable: a vibrant civil society that helped Georgia become a beacon of democratic progress in the region.

From Rose Revolution to “Russian Dream”: Georgia at breaking point with pivotal pro-EU protests

The fatal dependency: how Western money created the weapon to destroy democracy

For two decades, Georgian civil society lived on life support: US government funding. Independent media, NGOs, democracy programs—all relied heavily on American largesse because local businesses feared government retaliation for supporting critical outlets.

“This was mainly the US government funding because there was not enough advertising money in independent media,” Robakidze explains. Vulnerable to state pressure, “big business did not want to work with media outlets like this because they were investigating government corruption.”

The dependency created a catastrophic vulnerability. When Georgian Dream wanted to crush civil society, they had a ready-made weapon: the “foreign agent” narrative borrowed directly from Putin’s playbook.

But the irony runs deeper—and darker. Western funding didn’t just create the vulnerability; it actively trained the oppressors.

Georgian Dream created Western-funded strategic communication units across government ministries. “And then this communication in the crisis, when the crisis was approaching, was used against those who were actually protecting Western values—civil society, media, free media, etc.”

The absurdity was complete: civil society trained its own oppressors. “We were inviting representatives of this group to different trainings, on strategic communication, on public opinion research, and they learned the lesson really well. Maybe they were the best in their class, actually.”

The students became the masters, using Western-funded skills to dismantle Western values.

Playing fair while opponents cheated

Civil society’s commitment to democratic norms became another vulnerability. While democracy defenders insisted on fact-checking, verification, and due process, their opponents weaponized speed and fabrication.

During Georgia’s October 2024 elections, civil society deployed 3,000 trained observers who knew by 11 AM they were witnessing “the worst election in Georgian democratic history.” But while they spent the day meticulously fact-checking evidence of fraud, Georgian Dream simply declared victory at 8 PM.

“We struggled to communicate this on time because we were checking each and every case, double-checking it,” Robakidze recalls. “But we lost the battle of the very important, crucial minute.”

Civil society eventually proved the elections were fraudulent—no international observer recognized the results as legitimate. But Georgian Dream had already won by ignoring the verification process that constrained their opponents.

“We collected all this evidence… But we lost the battle of the very important, crucial minute,” Robakidze reflects. It revealed a global pattern: authoritarian forces exploit democracy’s commitment to due process, turning democratic values into democratic vulnerabilities.

Stolen election: how the Georgian Dream helped itself to 15% of all votes cast

Media massacre: systematic destruction of independent voices

The government’s media strategy went beyond funding manipulation—it became systematic annihilation. In April 2025, the Georgian Public Broadcaster fired two prominent journalists—Nino Zautashvili and Vasil Ivanov-Chikovani—after they openly criticized the channel’s editorial policy. Ivanov-Chikovani had stated live on air that the broadcaster’s editorial policy “fails to meet the public’s demands.”

The broadcaster’s supervisory board, headed by Vasil Maghlaperidze—a former deputy chair of the ruling Georgian Dream party—called for prosecutors to investigate journalists who criticized the channel’s coverage. The message was clear: dissent will be criminalized.

Since May 2024, more than 30 journalists covering the “foreign agent” bill have been targeted with anonymous threatening phone calls. Unknown individuals plastered posters on journalists’ homes and offices, denouncing them as “foreign agents” with messages like “There is no place in Georgia for agents.”

The new Foreign Agents Registration Act grants the state authority to criminally prosecute media outlets, NGOs, and individuals for failing to register as a “foreign agent,” with penalties of up to five years in prison. As one media executive warned: “We will work as volunteers as long as we can… But I cannot take any money from any donor past May 30, because I don’t want to go to jail.”

More than 70 journalists have been injured while covering protests, with some hospitalized. The systematic nature is unmistakable: this isn’t random violence but coordinated destruction of independent media.

The confession: “I was not fierce enough”

For Robakidze, the crisis forced brutal self-examination. Could civil society have prevented this catastrophe?

“I always ask myself: did I do everything I could to convince my colleagues and those with whom I worked closely that what is happening is dangerous, and this might lead in a very wrong direction?”

Her answer haunts her: “I think that no, I did not.”

She was part of the problem—attending conferences, sitting at tables with government representatives, participating in dialogues even as the warning signs mounted. “Maybe I was not fierce enough, and maybe the urgent situation that we have now would not have been needed if we started being really fierce and dramatic on the very first cases.”

The first red flag came just months after the peaceful 2012 transition, when Georgian Dream defeated Mikheil Saakashvili’s United National Movement in parliamentary elections. The victory was celebrated as a triumph of Georgian democracy—the first peaceful transfer of power in the post-Soviet space.

But the honeymoon was brief. On 17 May 2013—International Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia—a small solidarity gathering of maybe 50 people, mostly journalists and human rights defenders, planned to remember LGBTQI+ victims in Tbilisi’s city center.

Instead, they were attacked by a massive, organized mob, with things getting so out of hand that the 50 protesters needed to be bussed out.

For Robakidze, this wasn’t random violence—it was a test. “At that moment Georgia government had a really brilliant police structure. There was no way, no chance, if the state wanted to protect these people, that things could get so ugly and so violent.”

The attack was “visible that it was organized… And those people were having the blessing or green light from the government and Ministry of Interior.”

The red flag was a warning of things to come: 12 years later, the Georgian police disperses hundred-thousand-strong protests; the state’s repressive apparatus has been fully unleashed on the people.

More red flags followed. In 2016, Azerbaijani investigative journalist Afgan Mukhtarli was kidnapped from Tbilisi’s Freedom Square and appeared in an Azerbaijani prison. No footage existed. “We knew that there was no possibility without state interference for such things to happen.”

But civil society and international partners found it easier to focus on Georgia’s successes than confront uncomfortable realities—so they were ignored.

The lesson crystallized too late: “There is no small compromise with non-freedom. If you compromise that small thing, you definitely need to compromise the bigger thing tomorrow.”

Why Georgia will still win: the freedom advantage

Despite the catastrophic failures, Robakidze remains optimistic about Georgia’s ultimate victory. Her reasoning cuts to the heart of what separates Georgia from Russia and Belarus—and why this matters for democracies worldwide.

“Georgia was a democracy for 30 years. And we enjoyed the freedom of speech, freedom of arts, freedom of movement, everything,” she says. “We tasted freedom.”

Even under Soviet rule, Georgia maintained psychological independence. “Even during the Soviet Union, Georgia was still having that sense of freedom alive because of the language we were using, which was never Russian.”

This creates a fundamental difference from Georgia’s neighbors: “We are genuinely not part of the Russian thinking world.” The government’s target audience—those susceptible to pro-Russian messaging—consists mainly of “mostly older men in regions who had only good things happening in their early years” and “have the sentiments of the Soviet Union.”

But the crucial difference is ideological. Georgian Dream lacks what Putin possesses: an ideology, which makes long-term authoritarian consolidation questionable.

The government is “on their lowest level. Lowest approval ratings in their 12-year history.”

From dependency to independence: The silver lining

The loss of US funding, while painful, may have been necessary medicine. For the first time, Georgian civil society is learning to survive independently.

“Now, first time I see that really viable… society will support independent media and society will support civil society actions,” Robakidze observes. “Whatever happens right now is completely 100% financed by ordinary citizens who are just crowdfunding.”

This grassroots renaissance extends beyond civil society. “We also see for the first time big business also understanding the responsibility that if things go wrong in this part, we can die with them as well.”

The protests themselves represent this new independence. You cannot find “the industry or the sphere where the most prominent people are not part of the protest in Georgia.” All major theaters, singers, and composers have joined the streets. “These are theaters that young people are going to, and you cannot find a ticket for months if you want to attend a theater.”

Even government employees are risking everything. More than 200 public servants were fired simply for posting pro-European statements on Facebook—a purge that backfired by revealing the government’s desperation and creating martyrs.

Global warning: your democracy is next

Georgia’s crisis reflects a global phenomenon that Robakidze calls the “spirit of non-freedom spreading.” The mechanics are eerily familiar across continents.

“A lot of people in the world were living many years thinking that freedom is granted and guaranteed, taking freedom for granted,” she explains. “In Europe, in the US, in the West in general, they had this problem maybe even deeper than the Georgian society has.”

Western societies “allowed in their societies this darkness to spread without reacting to it when it’s needed.”

The warning signs are identical:

- Small compromises that seem manageable

- External funding creating dependency vulnerabilities

- Strategic communication training weaponized against democracy

- Media capture through economic pressure

- Civil society taking freedom for granted.

“Right now weather is the worst for beginner democracies,” she warns. But the crisis is a “wake-up call for not just for us, for societies who want to be democratic and consolidated democracies one day, but for everyone.”

The clock is ticking

As Georgia’s protests continue into their seventh month, the timeline offers a stark warning: democratic collapse can happen faster than anyone imagines. Eighteen months from EU candidate to authoritarian crackdown.

“There is never a bad time to think about your mistakes, and we can never be uncomfortable discussing the elephant in the room, because this elephant will never go anywhere,” Robakidze reflects. “And the only problem that this discussion creates is this uncomfortable feeling, which I think is very important—better experienced earlier than later.”

The uncomfortable truth: external funding made Georgian democracy vulnerable by creating dependency rather than genuine grassroots strength. But losing that crutch may have forced the authentic resistance needed to survive.

Georgia faces its ultimate test—not just of its democratic institutions, but of whether a society that truly tasted freedom can recognize and defeat authoritarianism when it matters most. The answer will determine not just Georgia’s fate, but offer crucial lessons for every democracy grappling with its own “spirit of non-freedom.”

For Robakidze, the fight continues: “We will not let Georgia slide back under Russia’s influence.” The question is whether the world’s other democracies will learn from Georgia’s mistakes before their own 18-month countdown begins.

Source link