Will Human-to-Human Bird Flu (H5N1) Be the Long-Awaited “Disease X?”

By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Influenza A virus subtype H5N1(“Bird Flu”)[1], which is global, rapidly spreading, and “highly pathogenic,” is now infecting cattle, and (in the United States) at least one human. (Bird flu first emerged in China in 1996 in geese; from a useful potted history). The New York Times asks: “Is Bird Flu Coming to People Next? Are We Ready?” The deck, and I’m throwing a flag for a gross violation of Betteridge’s Law: “Unlike the coronavirus, the H5N1 virus has been studied for years. Vaccines and treatments are available should they ever become necessary.” Well, let’s hope so. However, I’m reluctant to attribute the miserably inadequate performance of our public health establishment on Covid to the virus not having been “studied”[2].

Influenza has been around a long time. The literature is vast, and I’m not going to try to summarize it today. (I encourage readers to expand on the science as needed, or correct me.) Rather, I will focus on bird flu institutional players, press coverage of bird flu spread and tranmission in mammals, and spillover (“zoonotic transmission”) from birds to mammals to humans (we being also mammals). I will close with a quick look at whether “Bird Flu” could be “Disease X”, which is how the major players frame the problem — and, no doubt, the opportunities — of a really bad pandemic. (In theatrical terms, will the Covid pandemic end up being a complete play? Act One? Scene One of Act One? Hard to know.) Now let’s look at the players. (I’m doing them first so when they are quoted in the press, you know the sources.)

Institutional Players

Here is the mission statement for APHIS (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service):

The balance (contradiction) between health and economics is clearly visible, so it will be interesting to see which side APHIS comes down on in case of conflict. The “One Health” program is meant to paper this contradiction over, and maybe it does:

“One Health” is an integrated, unifying approach that sustainably balances and optimizes the health of people, plants, domestic and wild animals, and ecosystems.

The One Health approach recognizes that:

- the health of animals, people, plants, and the environment are linked, and

- all those involved in protecting animal, human, and environmental health must work together to achieve the best health outcomes.

Well and good, but I don’t think “One Health” has been put to the test of a national cull, either, with a dairy cow going for between $1,500 and $4,000

Here is the APHIS FAQ, “Detection of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Dairy Herds” (PDF, which I’ve gotta say at least reads better than the slop CDC so often dishes out. Some readers may wish to know the milk situation. Here are APHIS’s views:

Will there be a milk recall?

Based on the information and research available to us at this time, a milk recall is not necessary. Because products are pasteurized before entering the market, there is no concern about the safety of the commercial milk supply, or that this circumstance poses a risk to consumer health. Pasteurization has continuously proven to inactivate bacteria and viruses, like influenza, in milk.

Will there be a milk recall? Could the consumption of raw milk from these states impact human health?

FDA’s longstanding position is that unpasteurized, raw milk can harbor dangerous microorganisms that can pose serious health risks to consumers, and FDA is reminding consumers of the risks associated with raw milk consumption in light of the HPAI detections. Food safety information from FDA, including information about the sale and consumption of raw milk, can be found here.

Now let’s turn to the CDC. Here is their mission statement[3]:

CDC works 24/7 to protect America from health, safety and security threats, both foreign and in the U.S. Whether diseases start at home or abroad, are chronic or acute, curable or preventable, human error or deliberate attack, CDC fights disease and supports communities and citizens to do the same.

CDC increases the health security of our nation. As the nation’s health protection agency, CDC saves lives and protects people from health threats. To accomplish our mission, CDC conducts critical science and provides health information that protects our nation against expensive and dangerous health threats, and responds when these arise.

At least APHIS gestures in the direction of balancing health and economics; CDC does not (meaning, based on our experience with CDC, that they are doing exactly that). During Covid, CDC has operationalized its “fight” [snort] against SARS-CoV-2, after butchering testing, by fighting aerosol transmission tooth and tail, giving lethally bad guidance on masks, decreasing quarantine time at the behest of Delta (the airline, not the variant), hiding information on breakthrough infections in the vaccinated, failing to even attempt contact tracing, and minimizing the perception of tranmission at all times (the “Green Map”), and using the leadership to model unsafe behavior for the public (one imagines Mandy, maskless and smiling, swanning about a Confined Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO) fondling dead animals). In a word, CDC optimized its Covid strategy for capital at every turn, starting with restaurants and airlines, and continuing on with Big Pharma. If this is what CDC can accomplish while improvising, one hesitates to imagine what they could do with years to prepare! Meanwhile, one can hope that USDA’s APHIS is not as hopelessly corrupt at HHS’s CDC.

Here is a close reading of CDC’s guidance for workers on bird flu: “Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus: Identification of Human Infection and Recommendations for Investigations and Response“:

[1] N95s, at last! [2] “Close exposure” implies droplet dogma. If transmission is truly airborne, then workers should don N95s when they enter the facility. [3] Somebody tell HICPAC. Don’t health care workers need training? Seriously, couldn’t one conceptualize hospitals as a sort of CAFO?To reduce the risk of HPAI A(H5N1) virus infection, poultry farmers and poultry workers, backyard bird flock owners, livestock farmers and workers, veterinarians and veterinary staff, and responders should wear recommended PPE (e.g., the same PPE is recommended for persons exposed to any confirmed or potentially infected animals as for exposed poultry workers; for specific recommendations see: PPE recommended for poultry workers). This includes wearing an N95[1]™ filtering facepiece respirator, eye protection, and gloves and performing thorough hand washing after contact, when in direct physical contact, or during [2] to sick or dead birds or other animals, carcasses, feces, unpasteurized (raw) milk, or litter from sick birds or other animals confirmed to be or potentially infected with HPAI A(H5N1) viruses.

Workers should receive training on using PPE and demonstrate an understanding of when to use PPE, what PPE is necessary, how to correctly put on, use, take off, dispose of, and maintain PPE, and PPE limitations[2].

Bird Flu Spread in Mammals

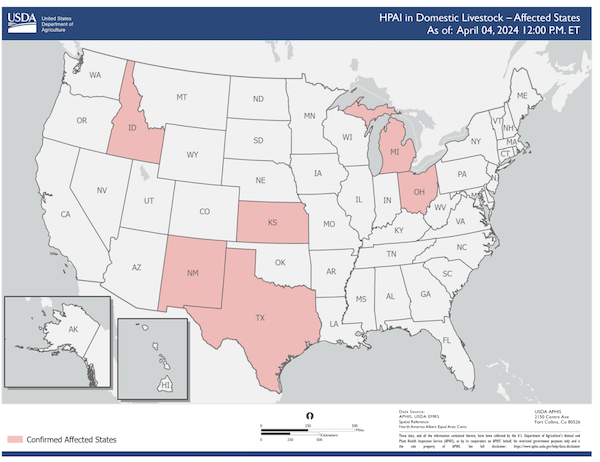

Here is a handy map on Bird Flu spread in cattle from APHIS (updated weekdays by 4 pm ET):

Commentary from the estimable FluTrackers:

Remember these are confirmed only. No one knows how widespread the dairy cow situation is. So this is a list of “at least”.

— FluTrackers.com (@FluTrackers) April 4, 2024

For mammals in general, I haven’t seen a map. Peter Hotez comments in the Houston Chronicle:

[B]irds are also transmitting H5N1 to mammals with increasing frequency. This could mean that the virus is undergoing mutations to adapt better to mammals and could ultimately spread more easily to humans, or even eventually cause human-to-human transmission. Over the last two years, avian influenza viruses have jumped to sea lions living along the Pacific Coast of South America and elephant seals. The deaths were widespread and devastating, disrupting entire ecosystems.

And nobody would have predicted that feral hogs would enter the picture:

Regarding this current episode in Texas cattle, I worry about our feral hog infestation — Texas hosts almost 40% of our nation’s feral hog population — and there’s a possibility that they could serve as animal reservoirs for “the big one.”

(“The Big One” being, I assume, “Disease X,” which we’ll get to below.)

More worrisomely:

My colleague Michael Osterholm, an influenza expert from the University of Minnesota, says he would be more worried if it were pigs infected with this H5N1, since they are vulnerable to both human and avian flu viruses. A co-infection with both kinds of viruses could allow these viruses to reassort in pigs and produce a new virus that could infect people. That sequence of events may explain how the influenza virus that caused the terrible 1918 pandemic is thought to have first arisen on a Kansas hog farm.

Bird Flu Transmission in Mammals

With Covid, I’m used to seeing serious epidemiological work on transmission (though as I said, I haven’t mastered the literature). The only material I’ve seen on bird flu transmission in mammals comes from dairy (and not beef) cattle. From Science, “Bird flu may be spreading in cows via milking and herd transport“:

The avian virus may not be spreading directly from cows breathing on cows, as some researchers have speculated, according to USDA scientists who took part in the meeting, organized jointly by the World Organisation for Animal Health and the United Nations’s Food and Agricultural Organization. “We haven’t seen any true indication that the cows are actively shedding virus and exposing it directly to other animals,” said USDA’s Mark Lyons, who directs ruminant health for the agency and presented some of its data. The finding might also point to ways to protect humans. So far one worker at a dairy farm with infected cattle was found to have the virus, but no other human cases have been confirmed.

USDA researchers tested milk, nasal swabs, and blood from cows at affected dairies and only found clear signals of the virus in the milk. “Right now, we don’t have evidence that the virus is actively replicating within the body of the cow other than the udder,” Suelee Robbe Austerman of USDA’s National Veterinary Services Laboratory told the gathering.

I’m surprised that the Science editors let “spreading directly from cows breathing on cows” go through as a description of aerosol transmission; this is simply a restatement of droplet dogma without the droplets. Aerosol transmission does not require “direct” “close contact”; like smoke, it will spread through the entire facility. From STAT, “Why a leading bird flu expert isn’t convinced that the risk H5N1 poses to people has declined“:

Of course, when we see this virus in a milking farm and you see incredibly high virus load in some milk cows and their milk, that is a new risk. Because I’m not sure how familiar you are with the milking procedures, but there’s very little that people do to prevent human contact with milk. During the milking process, there’s massive generation of aerosol formation….

There’s very little hygiene to protect the farmers that are milking.

Which, in a way, is encouraging. After all, if Bird Flu permeates the air, and a lot of humans haven’t caught it, then we aren’t on the way to a second 1918 flu. Unless and until H5N1 mutates and “spills over” to humans. [4]

All that said, it’s worth noting that on milking machines, dairy farmers vehemently disagree:

— Cindy Wilinski (@crwequine) April 6, 2024

Bird Flu Spillover to Mammals

BIrd flu binds to “receptors” in the respiratory tract. From NPR:

Unlike the seasonal influenza viruses that infects humans, H5N1 doesn’t have the ability to easily attack our upper respiratory tract, so it doesn’t tend to spread among humans.

However, the virus can bind to receptors in the lower respiratory tract. This may be one reason that people who develop respiratory infections with bird flu “can get very, very sick with severe pneumonia because those receptors are located deep in the lungs,” says [Angela] Rasmussen./p>

Of course, scientists are looking out for any signs that the virus has adapted to better target our upper respiratory tract.

And such “better targeting” has definitely appeared in non-human mammals (humans being, let us remember, mammals). From the Journal of Experimental Medicine, “Mammalian infections with highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses renew concerns of pandemic potential” (2023):

During 2020, a subclade of 2.3.4.4 viruses paired with an N1 NA called 2.3.4.4b emerged and started to spread to many parts of the world including Africa, Asia, Europe, and North and South America. These viruses have devastated wild bird populations and caused outbreaks in domestic poultry. Notably, they have also caused infections in various small mammals, including badgers, black bears, bobcats, coyotes, ferrets, fisher cats, foxes, leopards, opossums, pigs, raccoons, skunks, sea lions, and wild otters. Most of these have been “dead end” infections and are attributed to direct contact, from animals preying on and ingesting infected birds. However, two recent reports of H5N1 outbreaks in New England seals (Puryear et al., 2023) and on a mink farm in Spain (Agüero et al., 2023) mark the first H5N1 infections potentially involving mammal-to-mammal transmission, renewing concerns that the virus could be poised for spillover into humans. If confirmed, this is particularly concerning as the capacity to transmit between mammals has not been associated with H5N1 viruses previously, and it would suggest that clade 2.3.4.4b viruses may also have an increased capacity to cause human infection. In the absence of population immunity in humans and ongoing evolution and spread of the virus, clade 2.3.4.4b H5 viruses could cause an influenza pandemic if they acquired the ability to transmit efficiently among humans. From 2020 to date, six detections or infections in humans by clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 viruses have been reported to the WHO. Four were asymptomatic or mild, and two cases were associated with severe disease (World Health Organization, 2022).

However, the mode of transmission has not yet been established. From the European Food Safety Authority, “The role of mammals in Avian Influenza: a review” (2024). A systematic review:

The risk of infection was identified mainly as predation (or feeding) upon infected birds or contact with avian species. Evidence of mammal-to-mammal transmission in the wild is only circumstantial and yet to be confirmed. Cases of AI from the systematic review of experimental findings were discussed concerning epidemiology, pathology and virology. Knowledge gaps and potential pandemic drivers were identified. In summary, although a greater number of infections in wild mammals have been reported, there is no hard evidence for sustained mammal-to-mammal transmission in the wild. The factors contributing to the increased number of infections found in wild carnivores are not clear yet, but the unprecedented global spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses creates ample opportunities for intense, mostly alimentary, contact between infected wild birds and carnivores.

“Alimentary contact” is, I think, not likely in a CAFO, not even for Mandy. In terms of mutation, this layperson speculates that a mutation that allows H5NI to attack upper respiratory receptors in humans is the thing to watch for. From Nature, “Rapid evolution of A(H5N1) influenza viruses after intercontinental spread to North America” (2023):

From a public health perspective, the increased pathogenicity of the reassortant A(H5N1) viruses is of significant concern. However, this is tempered by the avian[5] virus-like characteristics of the viruses with respect to their receptor binding preference and their pH of HA activation. Modification of these characteristics are likely required to enable sustained human-to-human transmission

Paraphrasing, birds (“avian”) and mammals have different receptors in their respiratory tracts. To spread in humans, H5N1 must at least mutate to lodge itself in the receptors that mammals have. From Emerging Microbes & Infections, “HA N193D substitution in the HPAI H5N1 virus alters receptor binding affinity and enhances virulence in mammalian hosts” (2024), I can’t even with the jargon, but here is the key point:

The results revealed that the N193D substitution in the HA RBD altered the binding preference of the virus from avian-like to human-like receptors. More importantly, N193D has a profound effect on growth kinetics and virulence in chicken, mouse, and ferret models, as well as in human respiratory organoids. Our findings highlight the importance of continuous and detailed monitoring as mutations in avian influenzas viruses found in nature pose a great threat to human public health.

I’m not sure who’s doing that monitoring. It would be good to know.

Pigs, presumably including feral hogs, make good reservoirs for mutation because, if I understand this correctly, they have both avian and mamalian receptors. From the European Commissions Project FLUPIG, “Pathogenesis and transmission of influenza virus in pigs“:

Among all animals, the pig is believed to play an essential role in the influenza virus ecology, since it has been shown that (1) pigs are susceptible to all subtypes of influenza A viruses, including those of avian origin; (2) pigs have receptors for both avian and mammalian origin viruses, and thus represent an ideal vessel for viral reassortment or adaptation of an avian virus to the mammalian host.

Oh, and H5N1 can reproduce, at least in some mammals asymptomatically. From Emerging Infectious Diseases, “Influenza A (H5N1) Viruses from Pigs, Indonesia“:

Pigs have long been considered potential intermediate hosts in which avian influenza viruses can adapt to humans. To determine whether this potential exists for pigs in Indonesia, we conducted surveillance during 2005–2009. We found that 52 pigs in 4 provinces were infected during 2005–2007 but not 2008–2009. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the viruses had been introduced into the pig population in Indonesia on at least 3 occasions…. .

As for H5N1 spreading asymptomatically in those workers we didn’t direct to mask up properly, would we even know?

if H5N1 takes off in humans odds are it’s going to hit farm workers – underpaid, frequently undocumented – first and hardest, and we probably won’t know for several months. (even if people are brave enough to risk going to seek healthcare)

— noah (@additionaltext) April 5, 2024

Institutional Players and Disease X

I’m going to present a series of quotations about “Disease X” with the sources concealed by a “key” in the form of a bracketed number, thus “[0]”. I will then map the key to a value that is the name of the institution, so [0] might map to, say “National Nurses United” (to pick a non-lethal example). Here are the keyed quotes:

[1] “Disease X: A hidden but inevitable creeping danger”[2] “What is Disease X and how will pandemic preparations help the world?”An old adage says, “Prevention is better than cure.” Nothing exemplifies this idea better than “Disease X.” According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “Disease X represents the knowledge that a serious international epidemic could be caused by a pathogen currently unknown to cause human disease.”

Disease X is supposed to be caused by a “pathogen X.” Such a pathogen is expected to be a zoonosis, most likely an RNA virus, emerging from an area where the right mix of risk factors highly promotes the risk for sustained transmission.

The COVID-19 pandemic was not the first to wreak havoc on the world and it will not be the last. Thus, we need to prepare for the next outbreak as soon as possible.

[3] “DISEASE X – What it is, and what it is not”Disease X is not a specific disease but is the name given to a potential novel infectious agent.

It represents an illness which is currently unknown but could pose a serious microbial threat to humans in the future. It is necessary to be prepared because there is a vast reservoir of viruses circulating among wildlife which could become a source of a new infectious disease to which humans do not have immunity.

At the Davos summit on Wednesday, healthcare experts emphasised that preparing for Disease X could help save lives and costs if countries begin research and preemptive measures in advance of a known outbreak.

“Of course, there are some people who say this may create panic. It’s better to anticipate something that may happen because it has happened in our history many times, and prepare for it”, said WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who joined the panel.

[4] “Disease X: The Next Pandemic”Disease X is the name given by scientists and the World Health Organization to an unknown pathogen that could emerge in future and cause a serious international epidemic or pandemic.

No-one can predict where or when the next Disease X will emerge. What is certain, however, is that a future Disease X is out there and will, at some point, spill over from animals into people and begin to spread in a disease outbreak.

Miles from the nearest city, deep in the dark recesses of a cave in Guangdong Province, it waits. Perhaps it silently stalks from high in the canopies of trees nestled along the Kinabatangan River. Or it lies dormant in one of the thousands of species native to the Amazon. Disease X.

This is not science fiction, it’s real.

Disease X is the mysterious name given to the very serious threat that unknown viruses pose to human health. Disease X is on a short list of pathogens deemed a top priority for research by the World Health Organization, alongside known killers like SARS and Ebola.

(It may well be, that with its horrific mortality rate, that H5N1 is, in fact, Disease X (there are other candidates). But we don’t know yet.) Now, here are the keys:

[1] National Institutes of Health (NIH)

[2] World Economic Forum (WEF)

[3] Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI)

[4] EcoHealth Alliance

So I suppose I should welcome the great and the good being involved. Then again, have any of these institutions taken the slightest accountability for Covid? These are, after all, global elites; you’d think they’d take accountability for something (I mean, something besides making sure Davos was well-ventilated going forward). It’s good to think about and prepare for Disease X, no question. Are these the people we want doing the preparing? And if not them, who else? Man, I hate turning into “Mr. Pandemic.” It’s really stressful….

NOTES

[1] Here is CDC’s explanation of flu naming conventions. Type A viruses “are the only influenza viruses known to cause flu pandemics.” As for the H and the N: “Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes based on two proteins on the surface of the virus: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N).” [2] “Inadequate” unless you believe that CDC’s goal was, in fact, a human cull, a thesis that certainly passes Occam’s Razor. [3] I have been ploughing through Title 42 in an attempt to determine if the CDC’s mission is defined (“The CDC shall ____”). Interestingly, the mission of the CDC Foundation (the CDC’s privatized fundraising arm) is defined. Any readers with information on this point, please contact me. [4] It’s really noteworthy that, once again, CDC’s focus seems to be solely on vaccines. Heaven forfend that CAFOs — or, for that matter, feeding operations like brunch — should be interfered with in any way. Business as usual. [5] Interestingly, if I have this right, the eye contains avian-like receptors. Hence the conjunctivitis in Texas?APPENDIX The Bird Flu Vaccine

FDA Approves Seqirus’ Audenz as Vaccine Against Potential Flu Pandemic BioSpace:

Audenz is the first-ever adjuvanted, cell-based influenza vaccine designed to protect against influenza A (H5N1) in the event of a pandemic. The novel vaccine combines Seqirus’ MF59 adjuvant and cell-based antigen manufacturing. The vaccine is designed to be rapidly deployed to help protect the U.S. population and can be stockpiled for first responders in the event of pandemic.

Audenz was developed with the MF59 adjuvant. Which is believed to enhance an immune response from the body by inducing antibodies against virus strains that have mutated. The adjuvant reduces the amount of antigen required to produce an immune response, increasing the number of doses of the vaccine developed, so that a large number of people can be protected as quickly as possible, [Russel Basser, chief scientist and head of research and development at Seqirus] said.

Development of Audenz was supported by a partnership with the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Working with BARDA, Basser said they will be able to stockpile doses of Audenz in case of a pandemic outbreak.