Could These American Paratroopers Stop the Germans from Reaching Utah Beach on D-Day?

O n the evening of June 5, 1944, Louis Leroux, his wife, and their six children scrambled atop an embankment near their farm to investigate the sounds of distant explosions. Three miles south, Allied fighter-bombers were attacking bridges over the Douve River on France’s Cotentin Peninsula. In the fading twilight the family watched silhouetted warplanes peel away from the glowing tracers of German anti-aircraft fire that stabbed skyward. When the excitement ended, the Lerouxs returned home to bed, unaware that their farm would play a vital role in the Allied liberation of France.

Their slumber was disturbed a few hours later by the droning of low-flying aircraft. Gazing out their windows, they were startled to see descending parachutes. “They looked like big falling mushrooms,” recalled Madame Leroux. “We didn’t know what they were but could see that they were landing in the marshes.” When shrapnel from German flak shells pelted the roof, Madame Leroux and her husband gathered their children to take shelter in the stone stairwell.

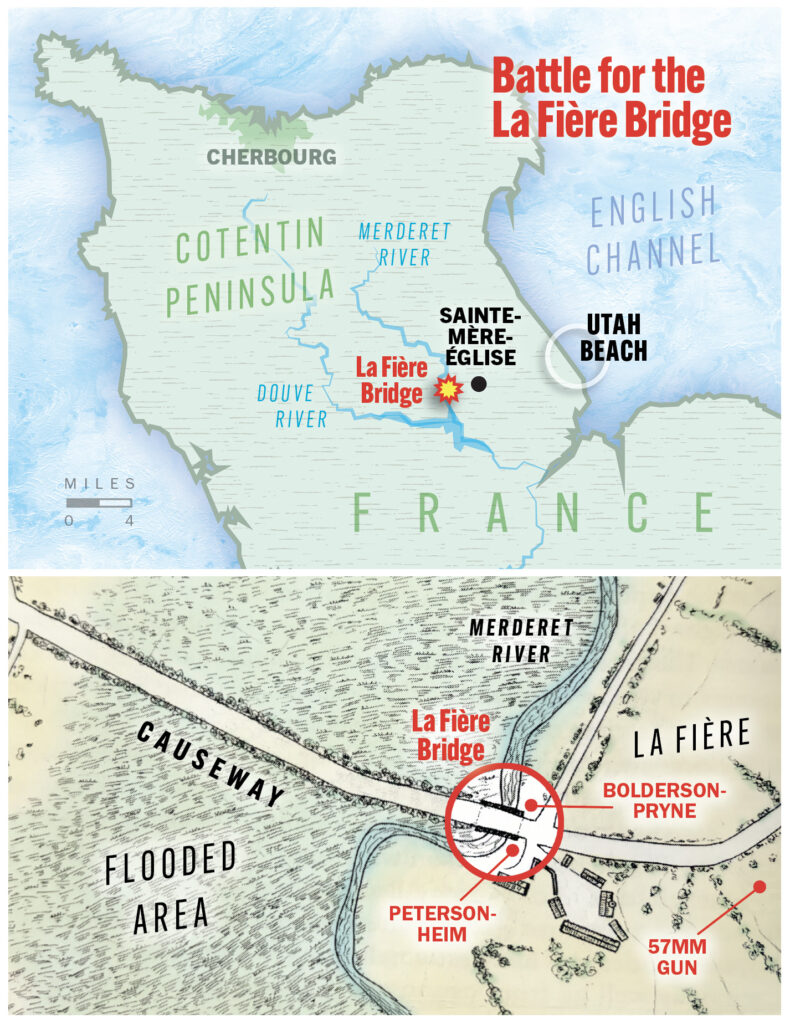

The farmstead sat on the east bank of the Merderet River, which bisected the Cotentin Peninsula north to south. The farm overlooked one of just two crossing points: the La Fière Bridge on the road to the village of Sainte-Mère-Église. While on the high ground, the family home was closer to the riverbank than originally intended thanks to the German occupiers who, recognizing the defensive potential of the landscape, had manipulated locks to flood the area with seawater. Rivers and streams had overflowed their banks to turn wide swaths of bucolic fields into swampland and a shallow lake.

At dawn on June 6, a platoon of Germans arrived at the Leroux’s farm. They searched the stables and occupied the house while the family retreated upstairs to the main bedroom. When gunfire erupted outside, the Lerouxs again scrambled for cover. Bullets cracked through windows, splintering shutters and ricocheting off interior stone walls. The staccato of German Mausers, MP40s, and MG42s echoed through the house as the occupiers fired back at the attackers.

(National Archives)

During a pause in the shooting, the family rushed downstairs, past wounded Germans sprawled in the kitchen, and into the wine cellar. Wanting to flee, they nudged open the external cellar door. Spotting a soldier—who they thought was British—they yelled, “Français! Français!”

He replied in French: “Stay where you are and close the door!”

Several hours later the door opened, and the same soldier commanded them, again in French, “Get out!”

The Lerouxs now realized the soldiers were American paratroopers. They questioned the French family to learn how many Germans were inside, and then the shooting resumed as the French family sought cover. “The noise took our breath away,” admitted Madame Leroux. The Americans were peppering the house with rifles and machine guns. The skirmish ended after a bazooka round exploded into the house and paratroopers sprinted in to herd the surrendering Germans out. In the lull that followed, the Lerouxs celebrated their violent liberation by gifting a bottle of Calvados brandy to the Americans. “They asked us to drink some first,” recalled Madame Leroux, “which we did. Then they all drank some.”

The paratroopers, there to seize the bridge and expecting a German counterattack, told the Lerouxs it was too dangerous for them to stay. The family packed food and blankets before walking to a neighbor’s home. During their exodus, they passed more American troopers heading to the bridge.

The La Fière bridge was the D-Day objective of the 82nd Airborne Division’s 1st Battalion of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment. Capturing the bridge intact was critical to the Allies’ plans: first, they needed to prevent the Germans from using it to move reinforcements against the landings at Utah Beach and second, they wanted the bridge to serve later as an artery for armor and infantry to break out from the beachhead toward the ultimate objective: the port of Cherbourg.

A member of the 505th later described the nighttime parachute drop they had made into Normandy as “a model of precision flying and perfect execution.” Pilots of the 315th Troop Carrier Group—veterans of missions in Sicily and Italy—had dropped their passengers right on target. Under the command of Lieutenant John “Red Dog” Dolan, Able Company assembled 98 percent of its troopers within an hour. The 505th’s sister regiment, the 507th, was supposed to land on the opposite side of the Merderet, but it was not as fortunate. Weather, anti-aircraft fire, and hopelessly lost pilots scattered them across 60 square miles.

With their drop zone just a half-mile from their objective, Dolan’s lead platoon pushed through the graying light of dawn and reached the Leroux’s farm in 30 minutes. The troopers immediately searched the bridge for demolition charges and put the German occupiers under siege. By mid-morning, with the help of paratroopers from the 508th PIR, the east side of the bridge was secure, but the scattered state of the 507th left the defense of the west side in a weakened state.

Major Frederick C.A. Kellam, the 1st Battalion commander, organized his men as well as troopers from other scattered units into a perimeter. The troopers of the 505th, most of whom had seen combat in Sicily and Italy, provided the backbone of his defense. As one of the veterans recalled, “We knew exactly what to expect on the upcoming mission: incoming mortar rounds, the terrifying German 88s, machine pistols, and one-on-one attacks against machinegun nests.”

The road past the bridge cut across the swampy marshland via an elevated, tree-lined causeway almost 700 yards long. Kellam’s men dug in on a gentle slope facing the river. The position was less than ideal as it left them in the open and in view of any Germans on the far side, but defending from the protected reverse slope wasn’t an option. One positive, though, was that any attack from the opposite side could only come across the narrow causeway.

(National Archives; Courtesy James M. Fenelon)

“Red Dog” Dolan positioned Able Company closest to the bridge: a platoon on each side, plus another in reserve 400 yards to the rear. Dolan’s heavy firepower consisted of three .30-caliber belt-fed machine gun crews and two bazooka teams dug in to the left and right of the bridge. He also positioned a 57mm anti-tank gun 500 feet back, at a bend in the road where it had a direct line of fire down the causeway. A platoon of combat engineers stood by to blow the bridge in the event of an enemy breakthrough. To prevent that, troopers blocked the far side of the bridge with Hawkins mines. “We placed our anti-tank mines right on the top of the road where the Germans could see them,” recounted Sergeant William D. Owens, “but could not miss them with their tanks.”

The troopers created an additional roadblock by pushing a German flatbed truck—disabled during the earlier firefight for the farmhouse—into the middle of the bridge.

A reconnaissance of the far bank revealed it was occupied by only a handful of 507th troopers rather than the expected battalion. Without radio contact and the planned-for support, the men led by Kellam and Dolan were on their own.

The first sign of trouble came at 4:00 p.m. when scout Francis C. Buck came hightailing it back across the long causeway. He’d heard spurts of gunfire followed by the unmistakable clanking of tanks. Close behind him were a few men from the west bank who were fleeing the German advance. Buck paused briefly at the two bazooka positions to give them a heads-up before sprinting to Kellam’s command post.

(National Archives)

The enemy heralded their attack with an artillery barrage, which lifted as four tanks rolled across the causeway. Following them were an estimated 200 infantrymen. The Americans held their fire—the fleeting glimpses of field gray uniforms darting between the trees wasn’t yet worth wasting ammunition.

The first tank—a Panzer Mk III—paused 40 yards short of the bridge. The commander, apparently spotting the mines, opened his hatch and stood up for a better look. One of Dolan’s machine gun crews squeezed off a burst at the tempting target and killed him instantly. With that, the American line erupted with rifle and machine gun fire.

The two bazooka teams went to work. Gunners Lenold Peterson and Marcus Heim abandoned their foxhole so they could aim around a concrete telephone pole. To their right, Privates John D. Bolderson and Gordon C. Pryne did the same. Just a few hours earlier, Pryne had been a rifleman, “But on the jump, one of the guys on the bazooka team broke his ankle,” he said. “They gave that job to me. I didn’t want it, really, but they said, ‘You got it.’”

The two teams pummeled the lead tank, which in turn fired a round at Peterson and Heim. It flew high, shattering the telephone pole. Dolan later admitted, “To this day, I’ll never be able to explain why all four of them were not killed. They fired and reloaded with the precision of well-oiled machinery.”

(National Archives)

The lead tank was hit by several 2.36-inch high-explosive rockets, one of which disabled a track while another briefly set it alight. Peterson and Heim advanced to get a better shot at the second tank—a captured French Renault R-35 painted Wehrmacht gray—which was some 20 yards behind the first. Heim later recalled, “We moved forward toward the second tank and fired at it as fast as I could load the rockets into the bazooka. We kept firing at the second tank, and we hit it in the turret where the body joins it, also in the tracks, and with another hit it also went up in flames.”

The 57mm gun fired as well and was subjected to heavy enemy retaliation. In the melee, two tank rounds punched through the glacis shield, and seven men were killed keeping it in operation.

A third tank now lumbered toward the bridge as German mortar shells pounded the American line. Although the first tank was disabled, the main gun and machine gun were still barking out shells. Rushing out from his foxhole, Private Joseph C. Fitt scrambled atop the first tank to toss a hand grenade into the open hatch and finish off the crew.

While the tank battle raged, the German infantry struggled to advance against the weight of American firepower. One paratrooper observed that the bunched-up enemy, seeking cover along the treelined causeway, “made a real nice target.”

(Agefotostock/Alamy)

With the German attack stalling, the two bazooka teams yelled for more ammo. Three men, including Major Kellam, scrambled forward with satchels of rockets. The trio was 15 yards from the bridge when another mortar and artillery barrage crashed in. Kellam was killed, and the other two men badly wounded, one mortally. Kellam’s death made Dolan the senior officer. His first action after taking command was to dispatch a runner to the regiment’s command post to advise them what happened.

Artillery continued to rain in. “They really clobbered us,” admitted Owens. “I don’t know how it was possible to live through it.”

Owens’ platoon was out front. When his radioman with the walkie-talkie took a direct shell hit, they lost contact with Dolan. “So, from then on, as far as we were concerned, we were a lost platoon,” said Owens. Anticipating another attack, Owens slithered from foxhole to foxhole collecting grenades and ammunition from the dead to redistribute to his men. “I knew we would need every round we could get our hands on.”

The enemy infantry rushed forward again, passing the knocked-out tanks and getting closer to Owens’ platoon, which poured fire into their ranks. “The machine gun I had was so hot it quit firing,” said Owens. He shouldered a dead man’s BAR, firing it until he ran out of ammo, then he switched to a second machine gun of a knocked-out crew.

Owens could hear another machine gun stitching the German flank and the plonking belch of a 60mm mortar lobbing shells along the causeway. Riflemen squeezed off shot after shot. It was getting desperate. “We stopped them,” Owens recounted, “but they had gotten within twenty-five yards of us.”

Just as the German attack failed, Colonel Mark J. Alexander, the regimental executive officer, arrived with 40-odd paratroopers he had managed to collect along the way. His inspection of the defenses confirmed they were set as well as could be expected. Shortly thereafter, the division’s second-in-command, Brigadier General James M. Gavin, arrived with men from the 507th. Gavin concurred with Alexander’s assessment, later recounting that Dolan’s troopers holding the bridge were “well organized and had the situation in hand.”

(Airborne and Special Operations Museum)

Alexander asked Gavin, “Do you want me on this side, the other side, or both sides of the river?”

After glancing at the far bank, Gavin replied, “You better stay on this side because it looks like the Germans are getting pretty strong over there.” The two officers agreed that attacking across the bridge would divide their manpower and might cost them the bridge in the face of a strong counterattack.

German shells continued to pummel the American positions. One shell exploded on the edge of a foxhole, burying the two occupants. Alexander helped dig them out and then sent them back to the medics.

First Sergeant Robert M. Matterson, who was directing the wounded to the aid station, said they were coming back in such numbers that he “felt like a policeman directing traffic.” Indeed, as the day ended, dozens of men flowed past while dozens more of their comrades lay dead, strewn across the battlefield.

Sunset gave way to darkness, with a bright moon that was occasionally obscured by scudding clouds. Throughout the night, the Germans periodically lobbed artillery shells at the Americans, while Alexander dispatched supply parties to scour the division’s drop zone for more ammunition.

At dawn, the rising sun released mist from the surrounding swamps and heralded the arrival of a squad of airborne engineers along with two more machine gun crews. Colonel Alexander warmly welcomed the men and directed them to dig in.

The additional firepower was much needed, but Alexander was still concerned about his available arsenal: “We had no long-range firepower other than machine guns. Well, we had one 57mm gun with six rounds of ammunition and a limited supply of mortar rounds, but this all had to be held in reserve for any serious effort the Germans might make to cross the bridge.”

Alexander’s mental inventory was interrupted when a group of paratroopers on the far side of the Merderet River attempted to wade across. He watched helplessly as German fire cut into the men sloshing through the water. A handful made it to safety, but most were killed and several of the wounded drowned.

The Germans preceded their next attack with intensified shelling, including tree bursts. Two more captured French Renault tanks were in the vanguard. Dolan’s 57mm crew held their fire—with only six rounds left they wanted a clear shot. But when the lead tank boldly geared onto the bridge, the 57mm crew cracked off a round. The shell struck the tank, sending it and its partner into retreat. Nestled in front of the anti-tank gun was Corporal Felix Ferrazzi, a radioman serving as a machine gunner. With a clear view down the causeway, he added to the mayhem with repeated bursts of fire into the advancing Germans. The gunners implored him to move due to the 57mm’s muzzle blast, but despite being wounded, Ferrazzi stayed put—until a mortar shell mangled his .30-caliber. The other Americans added to the wall of lead, especially Sergeant Oscar Queen, who estimated he fired 5,000 rounds from his belt-fed machine gun.

(Zachary Frank/Alamy)

Thirty minutes into their attack, the Germans floundered. They began their withdrawal as the paratroopers neared their breaking point. Dolan’s 1st Platoon was down to 15 men; one squad had just three troopers still standing. Owens sent a runner to report to Dolan: they were almost out of ammo and unable to repel the next attack; could they pull back? Dolan replied, “No, stay where you are.” He then scribbled a short message for the runner to relay to Owens: “We stay. There is no better place to die.” With his orders in hand, Owens organized what was left of his platoon.

But the Germans had had enough. They waved a Red Cross flag and requested a 30-minute truce to recover their wounded. Owens and his comrades used the time to bring up more ammo and determine who was still alive. Able Company had suffered 17 killed and 49 wounded; the battalion was down to 176 men. The exhausted Owens then sought a better view of the causeway. “I estimated I could see at least 200 dead or wounded Germans scattered about. I don’t know how many were in the river,” he said, “Then I sat down and cried.”

But the battle for La Fière Bridge wasn’t over. For the Allies to break out of the beachhead, the stalemate had to be broken. Later that evening, General Gavin relieved the battered 505th paratroopers with elements of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment. In a charge rivaling the Light Brigade, the glider men made a daylight assault across the causeway on June 9. Pushing through the pall of friendly artillery and withering enemy fire, they successfully occupied the far bank, while another group of 100 paratroopers swarmed in behind them to help secure the foothold. The road to Cherbourg was now open for Major General J. Lawton Collins’ VII Corps, but it came at a heavy cost. The 82nd Airborne had suffered 254 men killed and more than 500 wounded to seize, hold, and secure the vital bridge at La Fière.

The Leroux family returned to find their home in ruins and most of their livestock victims of the crossfire. They lived in the stable—as it had suffered the least damage—rebuilding their farm over the next five years. They moved back into their home in time for Christmas 1949.

“Our family celebrated,” recalled Madame Leroux, “happy, in spite of our misery, to all be back together without having suffered any dead or wounded, thanks to the American soldiers who fought to liberate and save us.”

Source link