2:00PM Water Cooler 1/15/2025 | naked capitalism

By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Bird Song of the Day

Brown Thrasher, Parc de la Survivance, Les Maskoutains, Quebec, Canada.

Contact information for plants: Readers, feel free to contact me at lambert [UNDERSCORE] strether [DOT] corrente [AT] yahoo [DOT] com, to (a) find out how to send me a check if you are allergic to PayPal and (b) to find out how to send me images of plants. Vegetables are fine! Fungi, lichen, and coral are deemed to be honorary plants! If you want your handle to appear as a credit, please place it at the start of your mail in parentheses: (thus). Otherwise, I will anonymize by using your initials. See the previous Water Cooler (with plant) here. From Desert Dog:

Desert Dog writes: “On the hike up to my daughters house in the four corners area of Colorado I pass this Bald Eagle roost where they can scan the valley below.”

Readers: Water Cooler is a standalone entity not covered by the annual NC fundraiser. Material here is Lambert’s, and does not express the views of the Naked Capitalism site. If you see a link you especially like, or an item you wouldn’t see anywhere else, please do not hesitate to express your appreciation in tangible form. Remember, a tip jar is for tipping! Regular positive feedback both makes me feel good and lets me know I’m on the right track with coverage. When I get no donations for three or four days I get worried. More tangibly, a constant trickle of donations helps me with expenses, and I factor in that trickle when setting fundraising goals:

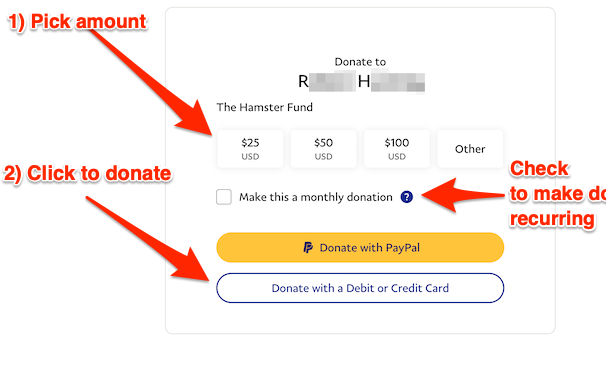

Here is the screen that will appear, which I have helpfully annotated:

If you hate PayPal, you can email me at lambert [UNDERSCORE] strether [DOT] corrente [AT] yahoo [DOT] com, and I will give you directions on how to send a check. Thank you!

Source link