CAR T therapy for multiple sclerosis enters US trials for first time

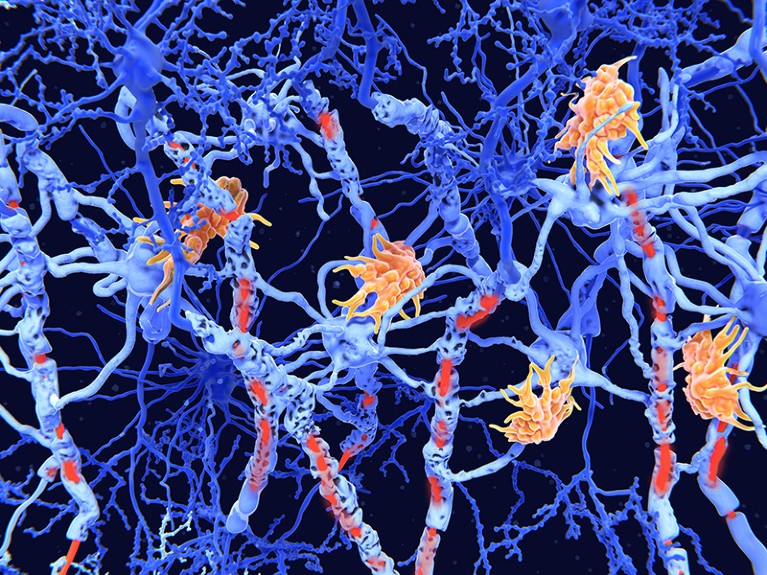

An artist’s impression of nerve cells (blue) showing damage (red) caused by the degenerative disease multiple sclerosis.Credit: Juan Gaertner/SPL

The first US trials of engineered cells to treat multiple sclerosis have started recruiting volunteers, raising hopes for a new therapeutic option for this devastating neurodegenerative disease and other autoimmune disorders.

Physicians already treat blood cancer with the engineered cells, called CAR T cells. But these living drugs are not yet approved for use in other diseases.

“We’re in uncharted territory here,” says James Chung, chief medical officer at Kyverna Therapeutics, a biotechnology firm in Emeryville, California, that is leading the charge to use these cells for multiple sclerosis.

Living drugs

CAR T cells are made by harvesting immune cells called T cells from people with diseases. The cells are then edited in a lab to produce proteins called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), enabling them to take on a target of choice. When CAR T cells are re-infused into the person they came from, they seek out and destroy their target.

Drug developers first jumped on the CAR–T cart to find a way to wipe out immune cells called B cells that grow out of control in blood cancers. Because B cells also contribute to various autoimmune diseases, cell therapies hold potential for treating these conditions, too.

‘It’s all gone’: CAR-T therapy forces autoimmune diseases into remission

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease, driven by misguided T and B cells that attack nerve cells. Neurologists have for decades treated MS with antibodies that target a protein called CD20, a marker of B cells. These antibodies kill these cells, keeping the immune system in check. But these therapies, when they work, slow rather than halt the disease.

Researchers have therefore turned to CAR T cells, and specifically to those that kill B cells carrying a protein called CD19. CAR T cells are better cell killers than are the antibodies, and seem to penetrate into tissues including the brain that antibodies can’t reach. More thorough depletion of these B cells, the theory goes, should reset the malfunctioning immune system — halting the brain damage that defines the disease.

Researchers in Germany are already running a small trial of CAR-T therapy for people with MS, in collaboration with Kyverna. Kyverna is also partnering with researchers at Stanford University in California on a US Phase I trial that is recruiting participants. Separately, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, is recruiting people in the United States into a bigger Phase I trial of its CAR T cells.

Immune reset

Neurologists have rebooted the immune system before, with promising results. In autologous haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation therapy, people with MS receive high-dose chemotherapy to kill off all their immune cells, followed by an infusion of their own stem cells to repopulate their immune system. But the risks and complexity of this therapy make it unattractive to biopharma companies, says BMS’s head of research, Robert Plenge, and it is not widely available.

CAR T cells could offer “a simpler way to reset the immune system”, says Plenge.

These cells might not be up to the task, says Mark Freedman, a neurologist at the University of Ottawa and a pioneer of the stem-cell transplantation therapy. Whereas chemotherapy can kill off all of a person’s T and B cells, CAR T cells wipe out only a subset of the B cells that contribute to the disease, he points out. But if the treatment is safe, he adds, it’s worth a try: “So much depends on safety.”

His biggest concern is brain toxicity, which can cause confusion, seizures and death and has been seen when CAR T cells have been used to treat cancer. The brains of people with MS are already inflamed, potentially exacerbating the danger, says Freedman, who consults for BMS but is not involved in the new trial.

Jeffrey Dunn, who is running the first trial of Kyverna’s CAR T cells in the United States, will be watching closely for brain toxicity, which he says seems to be linked to the number of B cells in circulation. B cells are everywhere in B cell cancers, but less abundant in MS. “We’re hoping that we see little toxicity,” says Dunn, a neurologist at Stanford University in California.

New frontiers

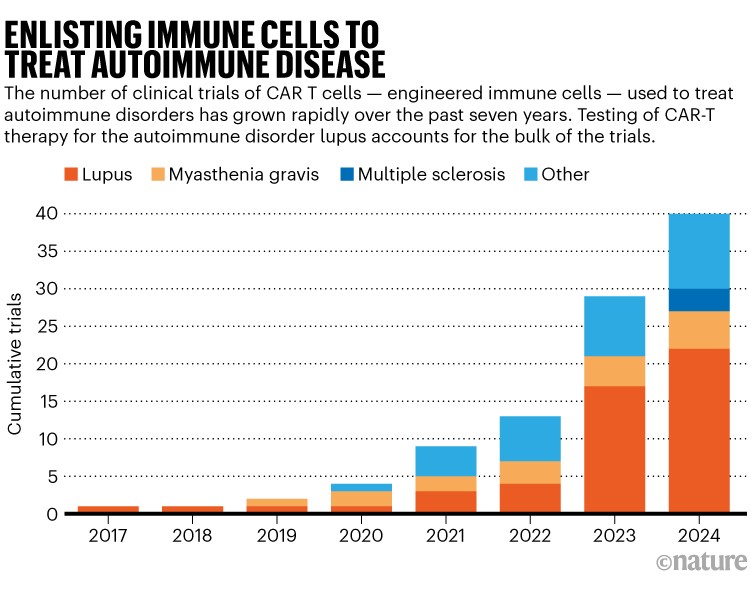

Drug developers are watching these trials and are poised to advance a full pipeline of CAR-T therapies that all act in similar ways. Preliminary clinical results already hint at life-changing potential in lupus, attracting a crowd of research teams (see ‘Enlisting immune cells to treat autoimmune disease’). MS could become just as competitive, says Dunn, if early data are supportive.

Source: clinicaltrials.gov

“I don’t want to get ahead of myself, but there’s a prospect here for a one-and-done therapy, which is pretty incredible,” says Dunn. “It could be an enormous paradigm shift.”

There are also practical challenges ahead. CAR-T therapy is gentler than autologous stem-cell transplant, but still requires a harsh ‘preconditioning’ chemotherapy to make room for the bespoke cells. Price is an issue, too: the hard-to-manufacture therapies currently cost up to US$500,000.

But researchers are working on next-generation CAR T cells that could be easier and cheaper to use, says Chung, and successes in autoimmune diseases are likely to spur on these efforts.

“We’re excited to do these trials, and to see where this goes,” says Chung.

Source link